It would be accurate to say that a significant portion of any aircraft’s value is in the logbooks. An aircraft can appear to be physically in pristine condition, but without the technical records to back that assertion up, the value of the aircraft is severely impaired. The relationship between airplane value and the quality of its records has been understood for many years, but in an era where aircraft leasing has become an increasingly attractive option, the accuracy of the documentation is more important than ever.

Aircraft leasing has become a significant factor in today’s aviation marketplace. In the 1980’s as little as 1.7% of the worldwide commercial fleet was owned or managed by lessors. Today lessors, led by industry powerhouses like GECAS and AerCap, hold the titles to over 40% of the global aircraft fleet.[1] By 2021, half of all the aircraft in airline service globally will be supplied by aircraft leasing companies.

Even as they have become more popular, the fact of the matter is that commercial aircraft leases are far from simple. Leasing aircraft, whether it is one airframe or one hundred, is a complicated legal, technical, and logistical exercise. Misconceptions commonly arise when operators begin to consider the technical requirements that are imposed on them when they lease aircraft. It is often not enough to comply with the “letter of the law” when it comes to airworthiness documentation and component traceability; for a variety of reasons, lease agreements often impose more restrictive covenants on air carriers that can add up to substantial downtime and costs on the front or back end of a lease. The goal of this mba Insight is to identify some of the common issues encountered by both lessors and lessees and to capture some best practices that can help airlines avoid additional costs and leasing companies to preserve the value of their aircraft assets.

The Three Stakeholders in Commercial Aircraft Leases

When considering the technical aspects of airworthiness records, it is fundamentally important to have an understanding of the stakeholders that must be satisfied. The aircraft operator is one obvious stakeholder; they require the aircraft to be a reliable and operative vehicle with which to conduct their business. They have a vested interest in maintaining the aircraft and its records in an airworthy condition that their national aviation authority (FAA, EASA, JAA, etc.) considers acceptable. The depreciation or resale of the asset is not their primary concern. By leasing the aircraft, the operator has shifted the residual value burden of the aircraft to the leasing company.

The second stakeholder in the lease is the lessor, who has interests that differ substantially from those of the operator. The lessor’s primary business is preserving the value of their asset—that is, ensuring that the aircraft will retain its value and generate rental income for as long a period as is possible. Not only does a leasing company have to concern itself with minimizing the depreciation of its asset, but it must consider the future transferability of the aircraft as well. The goal of the leasing company is to ensure that, at the close of the lease agreement, the aircraft can be re-marketed to as wide a customer base as is possible.

Retaining the ability to quickly redeliver their asset is why the commercial lessors often dictate that the aircraft and its technical records be in a state that exceeds the regulator’s airworthiness requirements at the end of the lease term. The operator may only have to meet one standard, that of their national aviation authority. The leasing company has to ensure that their product can comply with the highest global standards so that their customer base is not artificially limited to one geographic region.

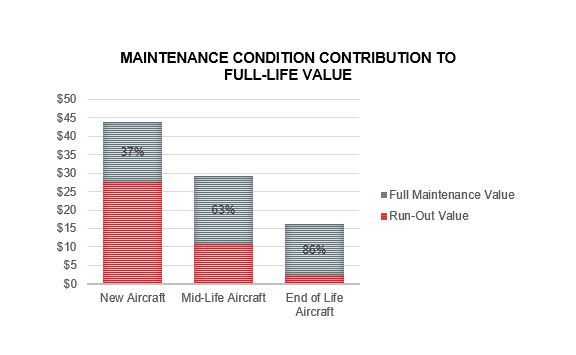

The third stakeholder is the financing party (or parties). While the leasing company has the primary and direct relationship with the aircraft operator; it’s rarely the case that the leasing company has 100 percent financial interest in the aircraft. A single aircraft may be collateralized by a bank, a consortium of banks, (or indeed other types of financial institutions). Financing parties therefore have risk centered on the leasing company’s continued ability to repay its debt obligations; and as the aircraft is held as collateral in many cases – the value of the asset itself. Financing companies have a vested interest in both the current and residual values, and watch both closely as values depreciate over time. An aircraft with sub-par technical records will have an adverse effect on current value; which if not corrected through the appropriate means will also affect the residual value. The leasing company provides the primary control, and mitigation measures when required.

Objectives for Stakeholders in Commercial Aircraft Leases

When an operator does not adhere to the technical records and maintenance conditions of a lease, or when an aircraft has significant gaps in maintenance program coverage, the value of the aircraft can be substantially affected. Problematic or missing records can represent an opportunity or an obstacle for a leasing company acquiring a used aircraft. Marc Wilson, mba’s Vice President of Technical, says, “What it boils down to is this – a sharped-eyed negotiator will use lapses in maintenance documentation as financial leverage. Or, it will force the leasing company to go back to the OEM for an expensive solution.”

The costs are real; mba’s experience indicates that airlines routinely spend upwards of $1 million on extra costs related to narrowbody aircraft returns to lessors. Overspending on widebody aircraft can easily exceed that amount by double. The majority of lease return costs and spending overruns are due to difficulties related to the accuracy and completeness of aircraft technical records.

Aircraft Technical Records are Essential to Aircraft Valuation

Accepting or preparing to return an aircraft to a lessor involves in-depth records checks. Aside from the basics that are common to every aircraft (airworthiness, registration, radio station license, and noise certificate), there are a host of maintenance records that need to be in a condition and format acceptable not only to the regulator but also to the leasing company. Among these maintenance records will be the status of life-limited components, hard time components, airworthiness directive and service bulletin compliance data, maintenance program data, and more. Lacking any of these elements will create delays and necessitate extra work that can cost tens of thousands of dollars.

Aircraft technical records are more than just the basics, however. Anyone having even a casual relationship with aviation realizes that aircraft are sophisticated machines, composed of hundreds of individual components, a significant number of which have specific flight hour or cycle limits before they must be replaced, overhauled, or subjected to other prescribed maintenance requirements. While the requirements for tracking the service life of these parts are generally well understood by operators, leasing companies rely on a higher standard of record keeping to preserve the value of their valuable assets. Instead of just tracking the number of flight hours or flight cycles, most lease arrangements require operators to adhere to the principles of back-to-birth and back-to-overhaul traceability.

Life-Limited Part Traceability

A significant part of any aircraft technical recordkeeping task is tracking the status of the life-limited parts on the airplane. Life-Limited Parts (LLPs) are those components that the OEM intends to be used for only a specified number of flight hours or cycles. When an LLP reaches the flight hour/cycle limit, it is no longer usable and must be permanently withdrawn from service and disposed of in a manner approved by the air carrier’s national regulatory body.

The problem with LLPs is that there is little consistency across the globe in methods used to track these parts. In the United States, the regulation that governs the tracking of LLPs is 14 CFR §43.10, which states in part that; “The part may be controlled using a record keeping system that substantiates the part number, serial number, and current life status of the part. Each time the part is removed from a type certificated product, the record must be updated with the current life status. This system may include electronic, paper, or other means of record keeping.”

The EASA regulations treat LLPs in a somewhat similar fashion. EASA M.A. 305 states that technical records must include “the component life limitation, total number of hours, accumulated cycles or calendar time and the number of hours/cycles/time remaining before the required retirement time of the component is reached.”

In reading the regulations, it is immediately apparent that the operative recordkeeping requirement is to track the part relative to its time or cycle limit. There are neither regulations that require specific evidence illustrating the accumulated time/cycles on the LLP such as engine logbook or shop visit logs, that a chain of ownership be established nor is there a requirement that previous owners’ show that the part was always kept in a secure environment. In the spirit of performance-based regulations, authorities generally grant operators a fair degree of latitude to choose a tracking method that works for them.

LLP component tracking and tracing is an area in which the commercial aircraft leasing industry is out in front of the regulators. Recalling that the primary concerns of aircraft lessors are to preserve the value of their asset and enable easy transferability to another lessee down the line, leasing companies have a significant vested interest in ensuring that they can prove the “chain of custody” of LLPs with a high degree of certainty. To that end, the industry standard has become more stringent than the regulatory standard; leasing companies, in particular, insist on back-to-birth (BtB) tracing for all LLP components installed in their aircraft.

BtB tracing of LLP components can impose significant time and work effort burdens on aircraft operators. If LLPs come directly from the component OEM, are installed on the wing, and simply stay there until their flight hour or cycle limit runs out, tracing the entire life cycle of the component is a relatively simple exercise. The reality is that airlines are continually removing, repairing, and replacing parts. In engines and APUs in particular, it would be an unusual situation for those highly complex modular assemblies that contain multiple LLPs to be returned to the lessors with the same serial numbers with which they were delivered to the operator. Instead, LLPs often make their way through various tail numbers during their life cycle, or even in between companies in the course of third-party MRO maintenance or parts interchange agreements.

BtB tracing involves retaining the original OEM Production Conformance Certificate or 8130-3/EASA Form One, a record of the operators or MROs that the component has passed through, along with a certified record of the hours that the part has been on the wing. Often, a statement of non-incident/accident is also required, which verifies that the component has not been exposed to saltwater, fire, severe stress, and has never been the root cause of an ICAO Annex 13-defined accident or incident.

Without these records, the overall value of the aircraft could be significantly impaired, and transfer between national jurisdictions could prove to be more difficult. The general rule around the world is that the aircraft owner, (the lessor in the case of leased airplanes), is ultimately responsible for providing proving the airworthiness of each LLP. Without BtB tracing, that level of certainty becomes difficult to attain.

Let’s look at an example of an engine having incomplete BtB LLP traceability, and how this might impair the value of an aircraft or the engine itself, and the costs associated with remedying the situation:

We have an engine, for which we cannot substantiate the BtB traceability on five LLPs. In our example, the engine has a CMV of $1,000,000; each of the LLPs has a list price of $100,000, a life limit of 20,000 cycles, and has 5,400 cycles remaining.

Let’s first examine the likely outcome, where the engine is being returned to the lessor as part of the redelivery of the aircraft:

The aircraft would be rejected (not accepted for return). The most likely scenario then would be that another engine (of at equal value and utility) would be substituted.

- Additional cost and expense for the Lessee (Airline) in arranging title transfer, removing and replacing the affected engine.

- Additional cost and expense for the Lessor, in marketing delays and possibly narrowing the market.

Now, let’s examine the likely outcome where the engine is being offered for sale for part-out.

The purchaser will realize that the five LLPs are of no use, as they cannot be re-sold as individual components. The price offered for the engine will be discounted to ascribe a zero-value to each of the five affected LLPs – resulting in a $135,000 price reduction.

Hard Time-Limited Component Traceability

Many of the parts on a modern commercial aircraft are subject to what is termed as “hard time” limitations. Landing gear assemblies are examples of hard time-limited components; it is often useful to think of these parts as assemblies since they are usually modular assemblies made up of a series of parts, some of which may be LLP components. The critical difference between hard time limited assemblies and LLPs is that components with hard time limits are intended to be overhauled, tested, and reused. They are designed by the OEM to last throughout the life cycle of the aircraft, so long as they receive the proper maintenance.

Given the “above the regulatory standard” applied by leasing companies to LLPs, it makes sense that hard time limited assemblies would be subject to the same scrutiny. The regulatory standard requires that operators track the flight hour or cycle status of hard time-limited parts. Leasing companies expect that any overhauled hard time components with which the aircraft is returned will come with sufficient documentation that shows not only when the overhaul was completed, but the details of that overhaul down to the “dirty fingerprint” record level. Additionally, the operator can expect to return the aircraft with a contractually agreed to amount of life remaining on both hard time-limited components and LLPs. Meeting this expectation requires careful maintenance planning and proper documentation on the part of the operator.

The reason that detailed back-to-overhaul records are so crucial for leasing companies is the same as the issues that drive their insistence on BtB records for LLPs: Asset value and the ability to redeliver the aircraft anywhere on the globe. Whether it is an engine, APU, or landing gear assembly, an overhaul involves complete disassembly and rebuilding of the component so that it is returned to a condition that is functionally equivalent to a new assembly leaving the OEM’s manufacturing facility. Old parts of the assembly may be replaced with new or repaired components. While it is permissible under FAA and EASA rules to use Parts Manufacturer Approval components in overhauls, that acceptance is not universal around the world. Thus, aircraft lessors generally insist on the use of OEM parts. OEM components ensure aircraft transferability and preserve value to the maximum degree.

PMA Components and DER Repairs on Leased Aircraft

The United States is unique in the world in that the FAA grants permission to manufacture aftermarket aircraft replacement parts under an authority called Parts Manufacturing Approval (PMA). The FAA approves these parts as being at least equivalent in quality to OEM components. While PMA parts are legal for use in U.S. flag aircraft, acceptance of PMA components for commercial aviation applications is not globally ubiquitous. Thus, lessors tend to avoid the use of PMA parts in their aircraft; the presence of non-OEM aircraft components could artificially deflate aircraft value, delay redelivery, and restrict the transferability of an otherwise airworthy aircraft.

The PMA parts issue is the backdrop for political and economic disputes as well. Some countries subsidize commercial aircraft parts manufacturers based within their borders. In doing so, they have shown a willingness to engage in protectionist trade strategies and use regulation to hamper foreign competition. Additionally, engine manufacturers, in particular, have made moves in recent years to tighten their grip on the aftermarket replacement parts marketplace; some engine manufacturers place severe restrictions on the use of PMA parts in the form of voided warranties or reduced levels of support.

The same issues surround the concept of designated engineering representative (DER) repairs. The FAA allows airlines and MROs to develop fixes for what would otherwise be unserviceable parts. Once these repairs are validated and deemed safe by an FAA DER, the operator or MRO can employ these procedures to render aircraft airworthy. Often, DER repairs can save an operator a lot of money in maintenance costs. Since DER repairs under the auspices of the FAA are not necessarily acceptable to foreign airworthiness regulatory bodies, leasing companies tend to avoid having these procedures employed in the maintenance of the aircraft that they own.

The bottom line is this: Both FAA PMA components and DER repairs create a situation where the aircraft may not be readily redeliverable to a customer on the other side of the world without significant additional costs and regulatory headaches. While some bilateral symmetries exist between the FAA and EASA, these agreements are not nearly comprehensive enough to accommodate leasing companies’ marketing needs. As such, the presence of PMA parts or a history of DER repair solutions can negatively impact aircraft valuation because it could render the aircraft much harder to place with another operator.

The Special Challenge of Bankrupt and Defunct Airlines: Gaps in Maintenance Program Coverage

When an airline ends up in bankruptcy or suddenly becomes defunct, it would stand to reason that lessors would be able to recover their aircraft along with the relevant technical records and then redeliver that aircraft to another customer reasonably rapidly. However, that is not the situation in which many lessors find themselves. An airline’s departure from business is rarely a well-organized activity. Key people leave their posts to pursue other opportunities. If the aircraft have stopped flying, dying airlines may see little use in fulfilling their contractual lease obligations concerning maintenance and record keeping. Finally, the aircraft themselves may be held hostage by other creditors: unpaid government taxes, fuel bills, airport fees, or MRO invoices may cause entities in some countries to attempt to hold onto the one part of the defunct air carrier that still has value—the aircraft themselves. The Cape Town Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment does provide a legal remedy for lessors to recover their aircraft, but exercising those rights can sometimes be a challenging endeavor. Additionally, there are many countries (especially in Africa and South America) that are not parties or signatories to that agreement.

As a lessor endures the slings and arrows of attempting to recover its assets, the clock is running. One of the major elements of commercial aircraft maintenance is continuity—that is the foundational principle that undergirds continuous airworthiness maintenance programs (CAMPs). These programs require that maintenance is done at specific intervals that may be defined in terms of days, months, cycles, or flight hours. When an airline becomes defunct, the continuous maintenance of airworthiness essentially ends. Marc Wilson from mba says, “you can generally go no more than seven days without a maintenance action on the airplane. Once you roll over seven says—certainly more than 14—you start to get into a problem. The lessor must get a plan in place with the type certificate holder relatively quickly.”

International Redelivery Considerations: EASA CAMO

A particular challenge related to the redelivery of leased commercial aircraft is meeting the maintenance records requirements of the jurisdiction where the aircraft will be redelivered. Some of the most stringent regulations exist in the European Union; the governing authority in the EU, EASA, prescribes that each commercial operator must engage a Continuing Airworthiness Maintenance Organization (CAMO). The purpose of a CAMO is to ensure that EASA maintenance continuity, quality, and recordkeeping requirements are met. Among the tasks handled by a CAMO are ensuring compliance with airworthiness directives, monitoring LLP flight hour/cycles, scheduling maintenance activities, tracking certification maintenance requirement completion, and incorporating STC requirements into the overall aircraft upkeep and record keeping picture.

In short, CAMO is the glue that holds the entire airworthiness puzzle together. Since the advent of CAMO as an EASA requirement for air carriers, other countries have begun to adopt similar regulatory models. CAMO-esque regulations have taken root in the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and South Africa, among other locations. According to Marc Wilson, “Latin American countries have begun to transition from a framework modeled on the U.S. FAA towards EASA-type CAMO systems. At some point, the regulations that lessors have had to accommodate in Europe will come into vogue in South and Central America as well.”

The stringent requirements of the EASA CAMO regulations are one of the reasons why lessors insist on pristine technical records when an aircraft is returned at the end of a lease. If a commercial aircraft is to be redelivered in the EU, all of the maintenance activities on that aircraft must be predicated on the receiving airline’s CAMO. The lessor does not have an EASA air operations certificate, so it is not permissible for them to do the work required and then deliver the aircraft to the lessee. Whatever maintenance is done must be completed under the auspices of the receiving air carrier’s CAMO, and the maintenance organization identified by the air carrier’s CAMO must complete the work.

Bilateral Agreements between the United States and the European Union do prevent situations where work on the aircraft has to be replicated, but only if the technical records indicate that the appropriate maintenance has been performed to the standards outlined in the receiving air carrier’s CAMO. If the records received from the previous operator of the leased aircraft are not up to the CAMO’s standards, expensive and time-consuming delays can result. The air carrier could be left paying lease payments on an airplane that they cannot fly without costly and unnecessarily redundant maintenance actions.

The Importance of Timing: Preparing for Redelivery

Optimally, the review of an aircraft’s technical records is an ongoing process that is conducted throughout its service life; the entire concept of continuous airworthiness holds rigorous records review as a foundational principle. However, real-world operational needs and time constraints often force air carrier maintenance organizations to make hard decisions about where to deploy their resources. In the case of aircraft that are operating under a lease, delays in conducting maintenance tasks required by the lease agreement or improper recordkeeping can result in increased aircraft shop time and unexpected costs.

Lessors can be expected to monitor the health of their asset while the operator is flying it. “Lessors generally will keep an eye on things via visits to the operator throughout the lease term,” says mba’s Marc Wilson. “These visits often consist of a high-level inspection of the aircraft and a snapshot review of the technical records.” Many lease agreements incorporate language that stipulates that the lessor will have the opportunity to inspect the aircraft annually or on some other specified schedule.

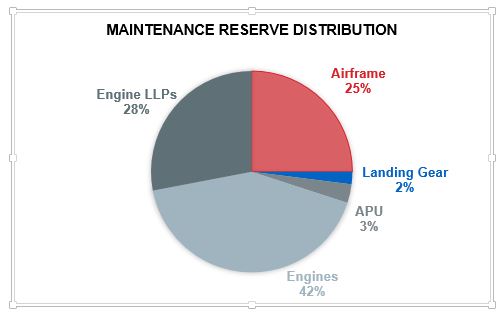

In addition to keeping up to date on the condition of the airframe and the aircraft’s records, operators leasing commercial aircraft can also expect that the lessor will pay particular attention to the amount of time remaining on critical hard time assemblies like engines, APUs, and landing gear assemblies. Most lease agreements set forth requirements for the time remaining on these components when the aircraft is returned to the lessor; 18 to 24 months of remaining life (or the flight hour/cycle equivalent) are typical values. Unless the operator plans carefully, these requirements can raise end-of-lease costs; airlines may find themselves in the position of replacing hard time components on the aircraft at an earlier stage than economics and regulations would otherwise dictate.

Engines and APUs demand particular attention in the run-up to redelivery. Many commercial aircraft leases have a mirror in/mirror out clause, which means the lessor expects that the aircraft will be returned in a state that closely resembles the condition the aircraft was in when it was delivered to the operator. Typically borescope inspections will be conducted of the hot and cold sections to ensure that the engines and APUs meet redelivery parameters. Additionally, the engines will require maintenance runs to document that they are still producing the rated thrust. Since lease agreements often stipulate a maximum number of engine flight cycles since the last shop visit, operators will likely need to incorporate off-wing maintenance planning into their redelivery preparation timeline. Since many operators contract out their engine work to third-party providers, beginning this work 6 to 12 months before the end of the lease is not uncommon.

As the aircraft approaches the end of the lease, operators would be well advised to bring technical representatives from the lessor into the information loop at an early stage. The last ‘C’ check event before aircraft return is one of the natural places to solicit lessor input; ensuring that there is operator and lessor concurrence on the scope of the work can go a long way toward avoiding unexpected expenditures. Communication also gives the operator the chance to fully utilize the final ‘C’ check interval, which could eliminate unanticipated end-of-lease downtime and an overall increase in operational expenses.

The general impression among lessors is that airlines tend to begin the process of preparing for aircraft later than they should, which increases the costs to the carriers and creates uncertainty in lessor redelivery schedules. IATA publishes a helpful guide that lays out a timeline of pre-redelivery and redelivery tasks. Their Guidance Material and Best Practices for Aircraft Leases document lays out a 12-month footprint of activities that can be broadly grouped into three categories:

Even though IATA’s guidance places records assembly at the end of the redelivery preparation process, it is a best practice to get started early. “The proper time to commence the records review—it’s somewhat variable,” says mba’s Marc Wilson. “A good starting point to begin this review is about 9 to 12 months prior to lease end. This also allows the lessor’s marketing staff to have some insight into the projected return condition of the aircraft, and allows their marketing plan to be geared accordingly.”

A Summary of Best Practices

Air carriers spend millions of dollars each year on lease returns, and much of the money spent is related to unforeseen costs that are incurred as a result of misunderstandings regarding redelivery requirements and recordkeeping. A good place for operators to begin is with a thorough understanding of the redelivery conditions outlined in the lease agreement and planning around those stipulations throughout the life of the lease. A clear concept of the lessor’s requirements regarding return condition, PMA parts, and DER repairs should drive maintenance planning and MRO selection. Communication with the lessor throughout the lease term is another way of avoiding redelivery hassles. Getting the lessor’s input on their interpretation of the lease conditions provides an opportunity to settle disagreements before it costs precious time and funds to do so.

As the date that the aircraft is to be returned to the lessor approaches, operators should put a plan and a team in place at the earliest possible stage. The IATA Guidance Material and Best Practices for Aircraft Leases publication provides a useful template for framing a strategy. Since there are many moving parts in any aircraft return, early and frequent coordination between operator technical staff, the lessor, and any MROs or third-party maintenance providers that will be engaged is essential to success. Finally, operators should ensure that they reach an agreement on the work-scope of the final “C” check before work begins. Failing to achieve this concordance could result in extended shop time and inflated costs.

[1] IATA. October 7, 2016. “To Buy or Not to Buy, That is the Question.” IATA Economics Chart of the Week. https://www.iata.org/whatwedo/Documents/economics/chart-of-the-week-7-oct-2016.pdf.

Download Insight PDF